Most people handle cash almost automatically, quickly glancing at the denomination before tucking it into a wallet or pocket. We rarely pause to inspect the details beyond the familiar faces, numbers, and designs.

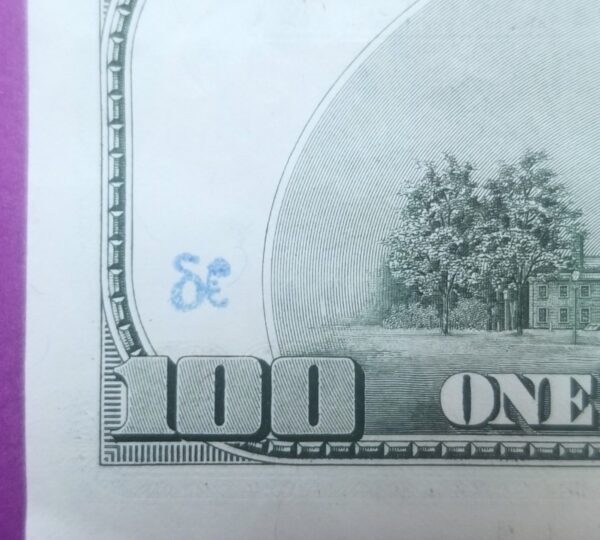

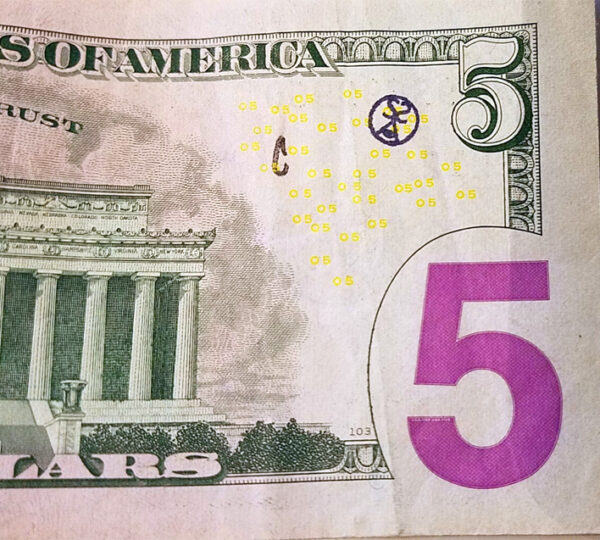

Occasionally, though, a bill will stand out because of a tiny, unusual symbol, an inked emblem, or a small stamped mark in the margin or near the portrait.

To the untrained eye, these markings can appear mysterious, even suspicious, prompting thoughts of secret codes, graffiti, or counterfeiting. However, these seemingly cryptic symbols often tell a story far richer than simple decoration—they are part of a centuries-old practice known as chop marking.

Chop marks are not damage or evidence of tampering. Instead, they represent a historical method of verification, a quiet form of authentication that has traveled across continents and centuries.

The practice originated in ancient China and evolved over time, adapting to different forms of currency and trade networks.

These small marks, stamped in ink or sometimes embossed, are a testament to the movement of money across borders and markets, reflecting trust, reliability, and commercial history.

Origins of Chop Marking in Ancient China

The origins of chop marks trace back over a thousand years to ancient China, where merchants and traders routinely dealt in silver, gold, and other forms of precious metal.

Before the development of modern banking systems, verifying the authenticity of coins and bullion was critical. A dishonest coin or impure silver could ruin a trade deal, damaging reputations and financial stability.

To mitigate these risks, merchants developed a practice of stamping coins with a personal or company mark—a “chop”—after verifying their weight and purity.

These stamps functioned as a signature of trust. Each chop indicated that a particular merchant had examined the coin and deemed it genuine.

Coins that accumulated multiple chops over time carried a growing reputation, signaling that several respected traders had accepted them. In essence, the more chops on a coin, the more trustworthy it was.

This system created a decentralized verification network long before standardized banking or government-issued certificates of authenticity became common.

Transition from Coins to Paper Currency

As economies evolved and paper money began to replace metallic currency, the practice of chop marking adapted. Paper bills are far more susceptible to counterfeiting, and many regions lacked centralized banking institutions capable of guaranteeing their authenticity.

Merchants and money changers filled this gap by continuing the tradition of marking currency with chops. Unlike their metallic predecessors, these marks were usually applied in ink rather than a punched emblem, preserving the fragile paper while still signaling verification.

During the 19th and early 20th centuries, international trade expanded rapidly, connecting markets across Asia, Africa, the Americas, and Europe.

The circulation of foreign currency became commonplace, especially the U.S. dollar, which emerged as the world’s most widely accepted currency.

With this global adoption came the spread of chop marks, particularly in regions where banking infrastructure was limited and informal methods of verifying bills were essential for smooth trade.

The Role of Chop Marks in Modern Currency Circulation

Today, chop marks are most commonly found on U.S. dollar bills circulating in parts of Asia, Africa, and Latin America. Countries like China, Hong Kong, Singapore, and Thailand have long traditions of using chops in commerce, and the marks have become a trusted method for quickly validating foreign currency.

Vendors, money changers, and traders apply these stamps as visual cues that the bill has already been inspected and approved for use.

In many cases, a bill may carry multiple chop marks, each representing a different merchant or institution that has confirmed its authenticity.

The designs of chop marks vary widely. Some resemble simple geometric shapes, such as circles, triangles, or crosses. Others take the form of miniature logos, stylized characters, or abstract symbols.

Despite their diverse appearances, these markings carry no hidden or secret meanings beyond their practical purpose: they indicate trust and verification.

A bow-and-arrow symbol, a star, or even a tiny character from a local script all serve the same function: to show that someone in the trade network has approved the bill.

How Chop Marks Affect Currency Value and Legality

For the casual user in the United States or other developed economies, a chop-marked bill may appear unusual, but it retains its full legal value.

Banks generally accept bills with chop marks without issue, recognizing them as a legitimate form of currency. From a financial perspective, chop marks do not damage the bill or diminish its purchasing power; they are simply historical and cultural markers on paper money.

For collectors, however, chop-marked bills can hold additional interest. Each mark tells a story about the bill’s journey, potentially tracing a path through multiple countries and hands over time.

Numismatists—collectors and scholars of currency—often seek chop-marked bills for their unique blend of history, art, and commerce.

In some cases, bills with well-documented chop histories can become collectible items, valued for the insight they provide into global trade patterns and historical economic practices.

Chop Marks as Cultural Artifacts

Beyond their functional role in commerce, chop marks serve as cultural artifacts, reflecting centuries of economic tradition. In regions where formal banking systems were limited or nonexistent, chops provided a decentralized means of ensuring trust.

They allowed merchants to operate with confidence, knowing that a bill verified by a respected colleague carried credibility. This informal system demonstrates how societies historically solved complex problems of verification and trust without modern technology.

Chop marks also offer insight into the global circulation of currency. A U.S. dollar bill with multiple chops may have traveled through markets in Southeast Asia, passing from one trader to another, each leaving their imprint.

The symbols document a hidden network of commerce, connecting continents and cultures through everyday objects. For historians, economists, and curious minds, each chop is a tiny fingerprint of global economic interaction.

Modern Applications and Persistence

While electronic payments, digital banking, and anti-counterfeiting technology have transformed currency verification, chop marking remains relevant in some markets.

Certain regions continue to rely on cash-heavy transactions, where quick visual inspection is preferred over technological methods. Chop marks offer an immediate, low-tech solution: a trusted merchant’s verification that can be recognized at a glance.

Even in today’s digital age, these small stamps maintain their symbolic weight. They are reminders that money is not just a medium of exchange but also a social contract built on trust.

They embody the practical ingenuity of merchants who, centuries ago, developed a system to ensure confidence and reduce fraud long before governments or banks could do so.

How to Recognize Chop Marks

If you are curious about chop marks, spotting them is relatively straightforward. Look for small symbols or inked designs, often near the portrait or on the bill’s margins.

They are usually discrete, sometimes only a few millimeters in size, but their presence is intentional. The marks rarely overlap with official security features, though in older bills, they may coexist with watermarks or other printing elements.

Collectors often categorize chop marks based on their appearance, the country of origin, and the number of marks on a single bill.

Some bills are heavily marked, indicating extensive verification and circulation, while others carry only one or two chops. Each variation tells a slightly different story about the bill’s past journey.

The Broader Significance of Chop Marks

In a broader sense, chop marks remind us that money is more than just a medium for buying and selling. It is a cultural artifact, a carrier of human trust, and a record of global interaction.

The tiny symbols etched or stamped on bills reflect centuries of economic ingenuity and cross-cultural exchange. They bridge past and present, connecting the modern user to the merchants, traders, and bankers who helped shape commerce as we know it today.

For the casual observer, a chop-marked bill may simply look curious or decorative. But for those who understand their history, each mark is a link in a chain of trust spanning countries and generations.

They illustrate how commerce adapts to local needs and how small innovations—like a merchant’s personal stamp—can have enduring influence.

Conclusion

The next time you handle a bill, take a closer look. Among the familiar faces and printed numbers, you may notice a small symbol—an arrow, a star, a stylized character—seemingly out of place.

That tiny mark carries a legacy: a story of trust, verification, and global commerce stretching back centuries to the markets of ancient China.

Chop marks are not just curiosities; they are living evidence of the human ingenuity that underpins economic life. Far from diminishing the value of a bill, they enhance it, connecting ordinary currency to extraordinary history.

In a world dominated by electronic transactions and digital money, chop marks remind us of the tangible, human side of trade. Each mark is a signature of trust, a nod to the merchants who ensured that commerce could flow safely and smoothly across borders.

They are subtle, often overlooked, but infinitely fascinating—a quiet record of how money moves, travels, and earns the confidence of people around the world.