My name is Jimmy. I’m thirty-six years old, and for most of my childhood, I was embarrassed by a coat. It was charcoal gray wool, heavy and outdated, with thinning fabric at the elbows and cuffs that had pilled from years of wear.

Two mismatched buttons sat awkwardly down the front — one slightly darker than the other — sewn on years apart when the originals had fallen off.

The lining had faded, and the pockets sagged. It looked tired. Worn. Like something the world had outgrown. When I was fourteen, image meant everything.

The right sneakers, the right backpack, the right brand name stitched across your chest. And there was my mother, standing outside school in that coat that looked like it belonged in another decade.

I made her drop me off a block away so no one would see her.

She never argued. She would just smile gently and say, “It keeps the cold out, baby. That’s all that matters.”

At the time, I thought she didn’t understand how things worked — how cruel teenagers could be, how fast judgments formed. I promised myself that one day I would buy her something better. Something beautiful. Something that made her look like she belonged in the life I planned to build.

My mother worked at a flower shop in the mall. She had worked there for as long as I could remember. The shop smelled like fresh lilies and damp soil.

She loved flowers in a way that seemed almost spiritual. “They’re the only things that are beautiful without trying,” she used to say. “They don’t compete. They just bloom.”

We didn’t have much when I was growing up. She worked two jobs for most of my childhood — the flower shop during the day and bookkeeping for a small grocery store at night. I didn’t realize how tired she must have been. I just knew she was always there when I needed her.

Every winter, she wore that coat.

It didn’t matter how old it looked or how worn it had become. She would brush lint from the sleeves, straighten the collar, and put it on like it was the most natural thing in the world.

When I landed my first job as an architect at twenty-six, I felt like I had finally kept my promise. I saved for months and bought her a cashmere trench coat — elegant, tailored, the kind of coat that quietly announced success. It was soft and warm and cost more than I had ever spent on clothing in my life.

I wrapped it carefully and handed it to her on Christmas morning.

She gasped when she opened it. Tears filled her eyes. She hugged me so tightly I could barely breathe.

“It’s beautiful,” she whispered.

The next morning, she wore the old coat to work.

We argued about it for years.

“Mom, we’re not that poor family anymore,” I would say, frustration creeping into my voice. “Please. Just throw it away.”

She would look at me with something unreadable in her eyes — not anger, not quite sadness, but something close.

“I know, baby. I know. But I can’t.”

She never explained why.

She wore that coat until the day she died.

Mom passed unexpectedly at sixty on a freezing Tuesday in February. A sudden medical emergency. The doctors said regular checkups might have caught it earlier. I visited most weekends. I called every evening. I told myself I was doing enough.

Grief has a way of exposing the things you tell yourself.

After the funeral, I went alone to her apartment to pack her belongings. The place felt smaller without her in it. Too quiet. The ticking of the kitchen clock sounded louder than it ever had before.

The coat was still hanging by the door.

Same hook. Same position. As if she had just stepped out to buy milk and would be back in ten minutes.

Something inside me snapped when I saw it.

Grief felt overwhelming and shapeless. Anger, at least, felt defined. Manageable.

We could have afforded better for years. She chose that coat. And now she was gone, and I would never understand why.

I pulled it off the hook, ready to throw it into a donation bag. But it felt heavier than it should have. The weight surprised me.

I ran my hand along the lining.

That’s when I noticed the stitching.

Deep inside the coat, hidden beneath the original lining, she had sewn pockets — large ones. I had never seen them before. They were carefully done, reinforced along the seams. And they were full.

My hands started to shake.

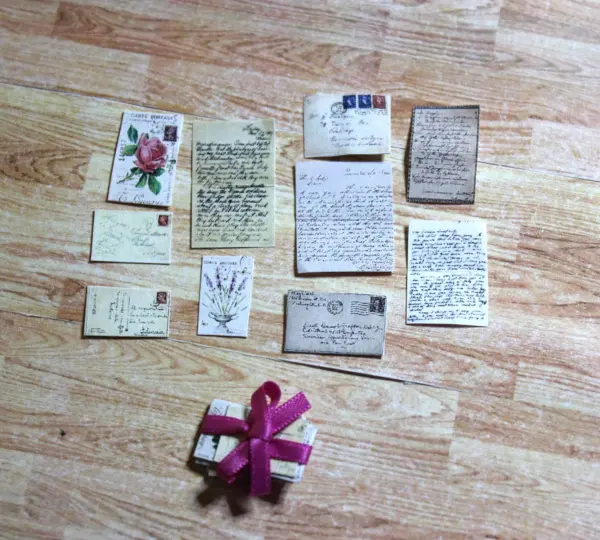

I reached inside and pulled out a thick bundle of envelopes held together by a brittle rubber band. The paper had yellowed with time. There were thirty envelopes in total, each one numbered neatly in my mother’s handwriting.

No stamps. No addresses.

I sat down on the floor by the door, the coat pooled beside me, and opened the first envelope.

“Dear Jimmy,” it began. “When you find these, I’ll be gone. Please don’t judge me until you’ve read them all.”

My father’s name, she wrote, was Robin.

She had met him when she was twenty-two. She had been walking through the town square carrying too many grocery bags when one split open, spilling oranges across the sidewalk. He had rushed to help her gather them. They laughed. He insisted on walking her home.

He never really left after that.

For two years, they were inseparable. They shared cheap dinners, long walks, quiet evenings. He dreamed of building something meaningful with his hands. She dreamed of building a family.

Then he received a job opportunity overseas — steady pay, real prospects, the kind of opportunity that could change everything.

He promised to come back.

The day he left was bitterly cold. She wrote that she had tried to act brave at the train station, but her hands wouldn’t stop shaking. Before boarding, he took off his coat — the charcoal gray one — and wrapped it around her shoulders.

“Just to keep you warm while I’m gone,” he had said.

She told him he would freeze.

He laughed and said he’d be fine.

Weeks later, she discovered she was pregnant.

She wrote to him at his forwarding address. She told him about the baby. About her fear and her joy.

No reply ever came.

She wrote again.

Nothing.

For years, she believed he had abandoned her.

She raised me alone. Two jobs. Long nights. Every winter in that coat, because it was the last thing he had ever given her.

When I was six, I had asked why I didn’t have a dad.

“Some dads have to go away,” she had told me.

That question, she wrote, broke her heart.

On the anniversary of the day he left, she wrote him another letter. She told him about my first steps. About how I clapped for myself when I stood without falling. She sealed it.

Instead of mailing it, she tucked it into the coat.

The next year, she wrote again.

And the next.

Thirty winters. Thirty letters.

I kept reading.

The early letters were raw and tender. She described my first day of kindergarten, how I cried when she left and how she waited in the car afterward, crying too. She wrote about my scraped knees and stubborn streak. About the way I lined up my toy blocks by size instead of color.

Around the ninth or tenth letter, the tone shifted. I had just won a local design competition at fifteen. She wrote that she had cried the whole drive home because she saw so much of Robin in the way I imagined buildings.

Then I reached the letter that changed everything.

While cleaning out an old box, she had found a newspaper clipping from the region where he had gone to work.

It was a small obituary.

Robin had died in a worksite accident six months after he left.

Before he ever received her letters.

Before he ever knew she was pregnant.

He hadn’t abandoned us.

He had never had the chance to return.

My mother had spent years angry at a man who had simply run out of time.

The letters after that were different.

She apologized to him in them. She told him she wished she had known sooner. She described every milestone in my life — my high school graduation, my college acceptance, my first architecture internship.

“He became an architect,” she wrote in one. “He builds things that last. You would have been so proud of him, Rob.”

I read that line over and over until the words blurred.

The final envelope contained a photograph.

My mother and a young man stood in a park, laughing at something outside the frame. They looked radiant. Hopeful.

There was one last letter.

She had discovered that Robin had a sister. Jane. Still alive. Living not far from where I grew up.

“I never reached out,” she wrote. “I was afraid she wouldn’t believe me. Afraid you’d get hurt. But you deserve to know you’re not alone in this world. Take the coat. Take this photo. Go find her.”

Three days later, I stood on the porch of a small cottage as snow fell steadily around me.

An elderly woman opened the door.

“Can I help you?”

“I think you’re Robin’s sister. Jane.”

“My brother died decades ago,” she said evenly.

“I know. I’m his son.”

She let me in, cautious but composed. I placed the letters and the photograph on her kitchen table.

“Anyone could find a photograph,” she said.

“My mother kept his coat. He put it on her shoulders the day he left.”

“My brother wasn’t married.”

“No,” I said. “But he loved her.”

She asked me to leave.

I stepped back outside into the snow.

The wind cut through the air. I stood there wearing the coat the way my mother had worn it every winter of my life.

Five minutes passed. Then ten.

The cold began to seep into my bones.

Finally, the door opened.

“You’re going to freeze,” she said.

“I know.”

“Then why are you still standing there?”

“Because my mother waited thirty years for answers she never got. I can wait a little longer.”

Her eyes moved to the coat.

She stepped forward and ran her fingers along the collar. They paused at a small repair near the seam — uneven stitching in a slightly different shade of thread.

She closed her eyes.

“Robin repaired this himself,” she whispered. “He was terrible at sewing.”

Her voice trembled.

“Get inside,” she said. “Before you catch your death.”

We sat by the fire with tea between us.

After a long silence, she picked up the photograph again.

“He has your eyes,” she said softly.

“It will take time,” she added.

“I know.”

“But I suppose you had better start from the beginning.”

When I left that night, I hung the coat on the hook by her door.

She did not tell me to take it back.

And I did not.

My mother did not wear that coat because she could not afford better.

She wore it because it was the last thing that had ever wrapped around her from the man she loved.

For years, I was ashamed of it.

Now I understand.

Some things are not worn-out fabric.

They are memory. They are history. They are proof that love existed — even if it did not last as long as it should have.

And sometimes, the heaviest things we carry are not burdens at all.

They are evidence.