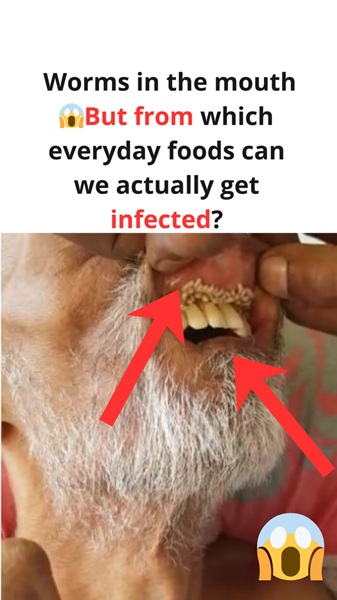

It might sound like something out of a horror film, yet oral myiasis is a documented and serious medical condition in which fly larvae (maggots).

Grow and survive inside the human mouth. Though extremely rare, the condition has been reported globally, especially in regions with poor sanitation.

High fly activity, and limited access to dental or medical care. While most people have never heard of it, oral myiasis is a stark reminder of how vulnerable the human body can become when hygiene, health, or circumstance create an environment conducive to infestation.

What is Oral Myiasis?

Myiasis is a parasitic infestation caused by the larvae of certain species of flies. These larvae feed on living or dead tissue, bodily fluids, or ingested food.

When this process occurs inside the mouth, it is referred to as oral myiasis.

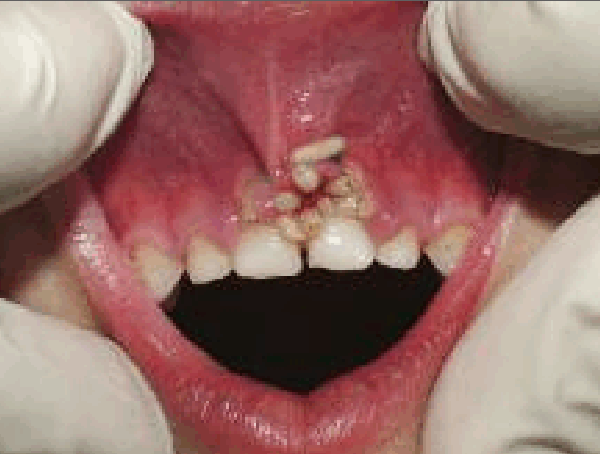

The condition may affect the gums, inner cheeks, tongue, palate, or lips, and in severe cases, it can compromise oral function, damage soft tissues, and even spread to adjacent areas.

Oral myiasis occurs in both children and adults, although the highest risk is seen in elderly, disabled, immunocompromised individuals, or those with poor oral hygiene.

People with paralysis, neurological disorders, alcoholism, advanced dental disease, or chronic illnesses are particularly susceptible.

The key factor is the presence of moist, necrotic, or exposed tissue, which provides a nutrient-rich environment for fly larvae to thrive.

How Oral Myiasis Develops

The infestation begins when certain species of flies lay eggs in vulnerable tissue.

These eggs are usually deposited in moist, unclean, or damaged areas of the mouth.

Flies are opportunistic and often target individuals who cannot maintain proper hygiene or who sleep with their mouths partially open, allowing them easy access. Some of the fly species commonly involved include:

Chrysomya bezziana (Old World screw-worm fly)

Cochliomyia hominivorax (New World screw-worm fly)

Musca domestica (common housefly in rare cases)

Lucilia sericata (green bottle fly)

Once laid, the eggs hatch into larvae within hours to a few days. These larvae burrow into the soft tissues of the mouth, consuming necrotic tissue, food debris, and sometimes living tissue.

This feeding causes progressive tissue destruction and leads to the hallmark crawling sensation, swelling, and discomfort associated with the condition.

Symptoms and Early Signs

Recognizing oral myiasis early is crucial. The condition often presents with gradual but noticeable changes in oral sensation and appearance, including:

A strange crawling feeling inside the mouth

Excessive salivation and drooling

Swelling and redness of affected areas

Difficulty chewing, swallowing, or speaking

Foul odor or bad taste in the mouth

Visible tiny white or yellowish larvae moving between gums, tongue, or inner cheeks in severe infestations

If left untreated, the infestation can expand rapidly, leading to necrosis, secondary bacterial infections, severe tissue destruction, and systemic complications.

In rare, extreme cases, larvae can invade surrounding facial structures, necessitating emergency medical intervention.

Misconceptions About Oral Myiasis

A common misconception is that oral myiasis occurs due to contaminated food. In reality, direct contamination from food is extremely rare.

The primary mode of infection is direct contact from flies landing in or near the mouth, particularly during sleep or in individuals with limited mobility or awareness.

Other contributing factors include:

Poor oral hygiene or untreated dental disease

Open sores, ulcers, or necrotic tissue in the oral cavity

Chronic mouth-breathing or inability to fully close the mouth

Debilitating systemic conditions (e.g., diabetes, HIV, or immune suppression)

It is important to emphasize that oral myiasis is not a result of “bad food” or neglect alone. Instead, it occurs when environmental and physiological vulnerabilities coincide.

Case Studies and Reported Incidents

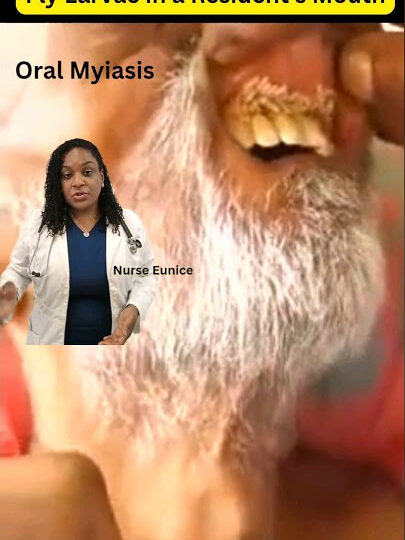

Though rare, documented cases illustrate the severity of oral myiasis.

One case reported a patient in a rural hospital whose mouth was infested with dozens of maggots, causing significant swelling, bleeding, and necrotic gum tissue.

In another documented incident, a bedridden elderly patient developed oral myiasis due to prolonged inability to maintain oral hygiene and unattended mouth-breathing during sleep, highlighting the vulnerability of certain populations.

Reports from India, Brazil, and Africa frequently describe oral myiasis in elderly or bedridden patients with chronic illness, often in communities with high fly density and limited access to dental care.

In these cases, maggot removal required careful medical intervention under local or general anesthesia, followed by intensive care to prevent secondary infections.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is typically clinical, based on visual observation of larvae and patient symptoms. Dentists or medical professionals may notice:

Visible larvae moving in the oral cavity

Necrotic or inflamed tissue surrounding the infestation site

Secondary bacterial infections or foul-smelling exudate

Imaging studies such as MRI or CT scans are occasionally used in severe cases to assess tissue involvement and ensure that deeper structures are not affected.

Laboratory tests may include parasite identification to determine the species of fly involved, which can inform treatment and prevention strategies.

Treatment

Treatment of oral myiasis is urgent and methodical, requiring both mechanical removal of larvae and medical management. The primary steps include:

Manual Extraction:

Each larva is carefully removed using forceps or tweezers.

Local anesthesia is typically used to reduce pain and ensure patient compliance.

Pharmacological Intervention:

Ivermectin, an antiparasitic medication, may be administered to kill larvae that are embedded deeper in tissue and not visible.

Antibiotics are often prescribed to control or prevent secondary bacterial infections.

Wound Care and Rehabilitation:

Affected tissues are disinfected and cleaned regularly.

In severe cases, surgical reconstruction may be necessary to restore gum tissue, inner cheek integrity, or even lips if extensive necrosis has occurred.

Dental Follow-Up:

Patients often require long-term dental care to restore oral function and aesthetics.

Prognosis

With timely and comprehensive treatment, most patients recover fully, though severe cases may require multiple interventions.

Early recognition dramatically improves outcomes and reduces the risk of tissue loss, systemic infection, or recurrence.

Prevention

Fortunately, oral myiasis is largely preventable. Key preventive measures include:

Good oral hygiene: Brushing teeth twice daily, flossing, treating gum disease, and regular dental check-ups.

Maintaining a clean living environment: Proper disposal of waste, minimizing fly exposure, and keeping sleeping areas free of insects.

Protecting oral wounds: Covering sores, ulcers, or damaged tissue to prevent fly access.

Monitoring at-risk individuals: Elderly, disabled, or unconscious patients should have daily oral care performed by caregivers.

Even simple precautions, such as using mosquito nets or window screens, can reduce the likelihood of flies contacting oral tissue.

Public Awareness

While oral myiasis is alarming, it is important to remember that it is extremely rare in populations with normal hygiene and access to healthcare.

Educating healthcare providers, caregivers, and vulnerable populations is critical to early detection and rapid intervention.

Recognizing the early signs — crawling sensations, excessive salivation, swelling, or foul odor — allows prompt medical action, preventing severe outcomes.

Conclusion

Oral myiasis represents a unique intersection of biology, hygiene, and human vulnerability.

It is a stark reminder that even in a modern, medically advanced world, parasitic organisms can exploit weaknesses in human tissue under certain conditions.

While the thought of living larvae inside the mouth is horrifying, understanding the causes, symptoms, treatment, and preventive measures can reduce fear and empower individuals to protect themselves.

The human body has remarkable defenses, but oral myiasis is an unsettling example of nature’s persistence and opportunism. Awareness, hygiene, and timely medical care remain the most effective tools for prevention and recovery.